“Instead of cursing, they prayed”

2015. április 15., szerdaAn exhibition called The Transcarpathian “Malenkij robot” was organized in memory of this tragedy in the Transcarpathian region of Ukraine (immediately next to the Hungarian border, in which a large number of Hungarians still live.) This exhibit commemorated the deportation of the Transcarpathian Hungarians in 1944.

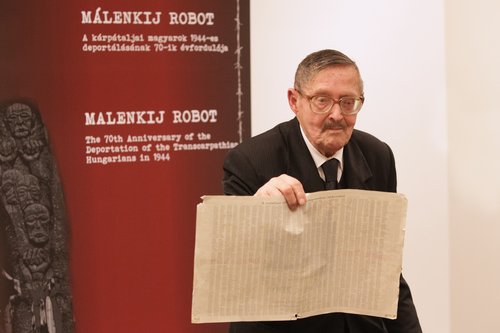

During the opening of the exhibition on the 29th of January, 2015, Lajos Gulácsy, the retired bishop of the Transcarpathian Reformed Church, who was one of the people deported to the Gulag, was recognized on the occasion of his ninetieth birthday. This exhibit was on display in the Hungarian House until the 26th of February.

“This topic is very important for us. We want to be widely aware of the troubled fate of this patch of land,” said Andrea Bocskor, the first Transcarpathian representative of the European Parliament and the former head of the Second Rákóczi Ferenc Transcarpathian Hungarian College Lehoczky Theodore Institute. (In the spirit of national unity for Fidesz-KDNP, in 2014 for Hungarians beyond the border, Andrea Bocskor also provided space on the list of the European Parliament and in the Hungarian EPP (European People’s Party)

At the end of 1944, the occupying Red Army in Transcarpathia collected and deported both Hungarian and German civilian men between the ages of 18 and 50, and forced them to work in labor camps for many years. Many of these men died from the inhumane conditions and never returned to their families. For the seventieth anniversary of this infamous tragedy, the “Malenkij robot,” the college historians from Beregszász assembled a Hungarian-English language exhibition about the Malenkij robot. This exhibit was displayed in the European Parliament in Brussels last year, by the favor of the Hungarian EPP, and then in February 2015, in the Hungarians’ House.

“This exhibition is not only about the Malenkij robot of 1944, but also the Ung, Ungocsa, and Bereg’s truncated counties of Maramures’ history of the twentieth century,” said Ildikó Orosz, the head of the Second Rákóczi Ferenc Transcarpathian Hungarian College. Everyone was reminded by the funny anecdote, that the Transcarpathian Hungarians witnessed several country changes in the last hundred years, even though they hadn’t moved from their village. But, underlying this anecdote is this sad reality: because the boundaries changed many times, the population lost their savings over and over, the Hungarian language was replaced by other foreign languages, and Hungarians became second class citizens.

“The catastrophic change of the country was the beginning of the wild communism,” claimed Orosz. The inhumane conditions, the prolonged suffering, and the forced labor until exhaustion caused the deaths of most of the laborers. It is estimated that only ten thousand returned from the forty thousand men who had been deported. There wasn’t a family in Transcarpathia who did not feel the lack of a male breadwinner. “There was no rehabilitation nor apology,” Ildikó Orosz recalled. “As long as this is not an accomplished fact, how could we build a happier Europe?”

Malenkij robot—little work

Long before the final peace agreements had been signed in Transcarpathia, the area was occupied by the Fourth Ukrainian Front of the Red Army since 1944. Transcarpathia had seen the introduction of the Soviet system: collectivization of farms, nationalization of property, the reduction of churches, and the isolation of national minorities. The tool was called “malenykaja rabota” (the Russian term); the Hungarians who did not speak Russian dropped some of the syllables, and the term became “Malenkij robot,” said Erzsébet D. Molnar, a historian and researcher at the Institute of Theodore Lehoczky, designer of the exhibition.

The reason give for the Melenkij robot, “the small job” or “the little work” was that a ruined region would be reconstructed. This purpose of the Melenkij robot was only a pretense for the collection of Hungarian and German men between the ages of 18 and 50, who were forced to sign up on the pain of court martial. In November 1944, the top-secret command of the Red Army issued an edict, No 0036-V, which commanded the collection of Hungarian and German men, herded them on foot into the Carpathian Mountains, boarded them onto trains, and sent them to labor camps throughout the Soviet Union.

The aim was two-fold: to increase the number of prisoners of war (because the officers required unrealistic figures) and they wanted to make it easier to claim Transcarpathia as a part of the Soviet Union by causing the collective guilt and isolation of the Hungarians and Germans in the region. In December 1944, more Germans (men and women) were deported to the mining towns in Donetsk, and in 1947, young people of military age were sent to forced labor camps. This was followed by the campaign against the intelligentsia and the wealthier peasants, artisans, bureaucrats, teachers, priests and pastors, and farmers, all of whom were sent to political prison camps. “Although we could not talk about it until 1989, the Malenkij robot is a key element in the Transcarpathians’ collective memory,” said the young historian. Nothing proves this more than the hundred or more monuments built by local communities who are trying to replace the memories and lost graves of cherished relatives.

“Peace and freedom are especially important today; therefore it is important that we hear what the witnesses from these Soviet forced labor camps in the Northern-Ural and Kazakhstan have to say,” said Thomas Wetzel, the Assistant Secretary of State of National Policy of the Hungarian government, during his opening speech. The Hungarian government designated a memorial day for victims of communism. The 25th of November is now the Memorial Day of Hungarian political prisoners and forced laborer who were deported to the Soviet Union, and the year of 2015 was declared to be the “year of memories” of the political prisoners and forced laborers who had been deported.

Heavenly Treasure in Transcarpathia

“Therefore in these ninety years of my age, I can talk about so many things. I can tell not only [of] the pain and suffering, but also [about] the joy and the beauty. In Transcarpathia, alongside a lot of tragedy, there was God’s blessing, which is still present today, because people live in small ways but still seek after the kingdom of God,” said Lajos Gulácsy, the retired bishop of the Transcarpathian Reformed Church. The Soviet authorities viewed his pastoral work with disfavor and took action against him, and he spent seven years in Kazakhstan. He then escaped from the forced labor camp to Debrecen, Hungary, and then returned to Transcarpathia, where he was renewed and became a tool for re-awakening in the area. “The [labor] camp was not only for suffering, but also as ‘God’s educational school,’ “ Gulácsy said.

“The reconstruction [of the ruins] was a lie; in fact, they wanted to destroy the people. It was the work of the devil, but God still blessed Transcarpathia with some special grace. In that great pain, people, instead of cursing, they prayed. They could understand the difficult times as a formation, not punishment. It was their resources,” said Gulácsy.

The retired bishop also talked about the life that is not easy even today in Transcarpathia. In the eastern part of the country, people have turned against each other, who had lived together as brothers and sisters. In this tense situation, he emphasized the importance of modesty and peacefulness. (We previously reported about the Ukrainian armed conflict in connection with this situation in Transcarpathia.)

Many of the speakers also greeted Gulácsy’s ninetieth birthday. He said, “I am ninety years old only on paper; in fact, I do not feel so old, because I have hope.” The retired bishop is still actively serving, for instance, in the nursing home in Beregszász. “It may be worth a happy old age,” he confessed, “but not enough to just believe only that Jesus is waiting for us and is preparing for us the kingdom of God, but [that we] also must be prepared to work for God’s kingdom on earth.” The retired bishop said that he undertook this journey to Budapest to tell his audience: “God is with us, and [I want] to encourage everyone to not be afraid of tomorrow, but to do everything on our own site for the Kingdom of God.”

Written by György Feke

Photos: Vargosz

English Version: Carolyn Otterness, Bianka Bénó

Contact us

Click here if you are interested in twinning.

Reformed Church in Hungary

Address: H-1146 Budapest, Abonyi utca 21.

PO Box: 1140 Budapest 70, Pf. 5

Email: oikumene@reformatus.hu

English, German and Korean language services in Budapest

Links

Recommended articles

-

Pastoral Letter in the Light of the Pandemic

Bishop Dr. István Szabó sent a pastoral letter of encouragement to the ministers serving in RCH’s congregations, expressing his gratitude for the persistence and creativity of the pastors.

-

RCH Joins in Pope's Call for Prayer

RCH published the call on congregations to join the initiative of Pope Francis, supported by ecumenical organisations, to unite in praying the Lord’s Prayer on Wednesday, 25 March, at noon.

-

English Speaking Worship Services Online

Each Sunday at 11 AM (CET) the St. Columba's Church of Scotland in Budapest, the international community of RCH invites you to join the worpship service on its facebook page.

-

Test of Humanity and Companionship

Reformatus.hu asked Dr. György Velkey, Director General of the Bethesda Children’s Hospital of RCH about the challenges of health care workers and ways of prevention against the pandemic.

-

All Church Events Suspended

In light of the coronavirus the Presidium of RCH requested congregations to suspend all church events with immediate effect. Beside restrictions, it calls for prayer, sobriety and responsibility.